|

By Danny Anderson

John Milius helped define the 1980’s when he cast Arnold Schwarzenegger in Conan the Barbarian. The 1982 film jump-started the career of one of cinema’s most iconic action stars, and the epic brought to the screen a violent swagger that made it an instant cult classic. The film was merciless, cruel, and ever so chauvinistic. If ever a film flaunts the conventions of political correctness, this is that film. Given all that, one might think that movie has aged badly and become reduced to a mere nostalgic curiosity, or, worse yet, only a cinematic pilgrimage for Proud Boys and devoted acolytes of Richard B. Spencer. I say to you today that this is not the case. Conan the Barbarian has become, to our collective cultural shame, more relevant than ever. Make no mistake: this is still a very fun movie and its classic soundtrack works with its visuals and campy, committed performances to create a shockingly thrilling experience. But what I want to focus on here is how the film’s politics map so neatly upon our own in 2020. First, there’s the civilization itself. Conan is born into a world in which the old orders have disintegrated. What has emerged in that vacuum is a combination of warlords and mysticism. In the figure of James Earl Jones’s Thulsa Doom, the mystic becomes warlord, and his snake-cult of personality spreads across former empires attracting young neophytes in hoards, undermining the very foundations of the old kingdoms. It should be fairly obvious that I’m drawing a parallel between Thulsa Doom’s warlord mysticism and the rise of populism and neo-fascism. For example, Donald Trump has subverted the old political institutions on the backs of not one, but two religious cults: the Christian nationalism of Evangelicalism and the secular messianic faith of QAnon. Trump, like Putin, is no less a snake-king than Thulsa Doom. And on the subject of snakes: in the last decade, the colonial era “Don’t Tread on Me” flag has become increasingly ubiquitous among certain groups. Whatever the origins of the flag are, people who fly it now signal an allegiance to an American micro-culture: militias, anti-masking, gun rights, and so on. This is merely a tip of the Balkanized iceberg that our society has become. We see it every day with variations on the American flag. Blue lines, red lines, colorless, colonial, fringed. And that Confederate flag, of course. It seems each group has its own tribalistic version of America to pledge allegiance to. Like Thulsa Doom’s symbol of two snakes facing one another, these flags are symbols of our modern gods, and everyone must choose their own object of worship, their own proverbial Crom, Mitra, or Set. The many gods of Conan’s Hyborian landscape are but one point of connection to our contemporary Balkanization. Conan’s debate with Subotai about whether Crom or The Four Winds are greater gods can be seen as a metaphor for our own many variations on the Black Lives Matter/All Lives Matter confrontation. Trump, for all his faults, is not the cause of this fracture, but another function of it, in spite of fantasies of a “return to normalcy.” Like Thulsa Doom, he has merely figured out how to rally his many tribes. Our civil discourse has collapsed. Hear the lamentation of the women. Blogger bio: Danny Anderson teaches English at Mount Aloysius College in PA. He tries to help his students experience the world through art. In his own attempts to do this, he likes to write about movies and culture, and he produces and hosts the Sectarian Review Podcast so he can talk to more folks about such things. You can find him on Twitter at: @DannyPAnderson. The Pavilion Blog is the companion blog of The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp Studies. It features brief, conversational reflections related to Robert E. Howard at around 500-600 words. Interested in contributing? E-mail the editors at [email protected] 8/20/2020 A Brief Publication History of The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp StudiesRead Now By Luke E. Dodd

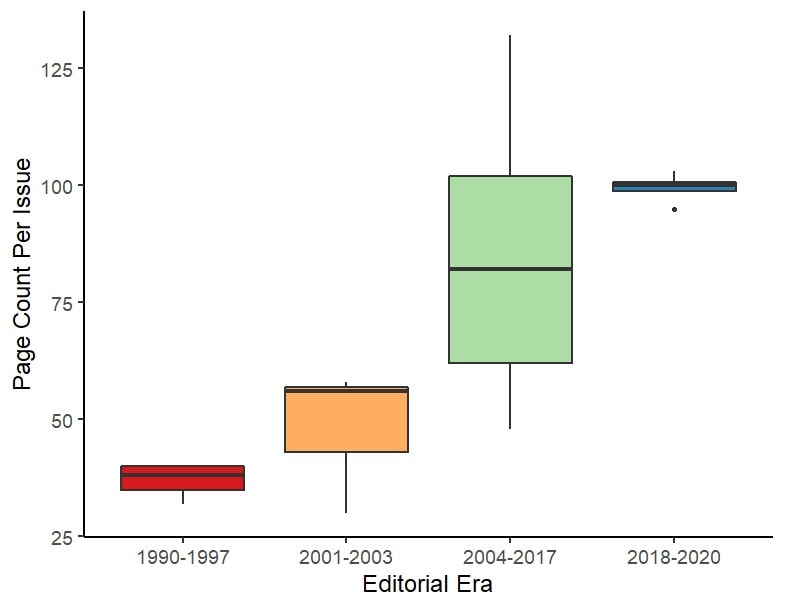

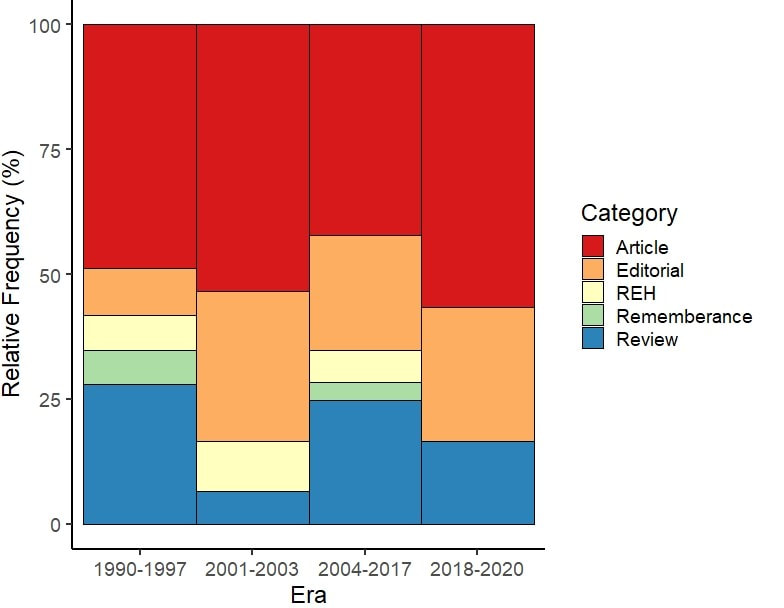

(Editors' Note: This is a preview of a larger study Dodd is conducting. The full study will be made available on our web page in December. Figures appended. JRC and NE) Publication of The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp Studies (hereafter, TDM) dates to August of 1990. Over more than 30 years, this journal has provided over 1,800 pages of content both for and from the Robert E. Howard fandom. To date, TDM has spanned 24 issues. Given the long tenure of this publication, lead editorial efforts have shifted over the history of TDM. Across all editorial eras, the publication rate of TDM has been 0.9 ± 0.2 (mean ± SE) issues per year. However, TDM has maintained a rate of 1.3 ± 0.4 issues per year since the landmark 25th anniversary issue, and since 2019 the journal has maintained a twice-annual publication schedule. Along a similar trajectory, the page count of any given TDM issue has increased dramatically over the years (see Figure 1 above). While the length of TDM has averaged 75 ± 6 pages across all issues, the journal currently hews consistently to a length of 100 pages per issue. These metrics indicate substantial growth of the journal across multiple decades. Across the full tenure of the journal, the majority of all entries in TDM have been either scholarly articles (47%) or reviews of published works (22%). Authorship of these pieces of criticism has varied widely over the decades, and serves as a testament to an inquisitive, vocal fandom that includes both established members of the field as well as newcomers to works of Robert E. Howard. Indeed, 63 individuals have contributed scholarly articles, notes, and reviews to TDM. Considering these, the most published contributors to TDM include Charles Hoffman (10 entries), followed by Rusty Burke (9 entries) and Dr. Charles Gramlich (8 entries). Editorial materials in TDM (21%) have spanned a variety of topics, and include not only prefatory remarks, but occasionally interviews, opinion pieces, or special features. Considering general trends across editorial eras, scholarly articles and notes tend to provide about half of the total contributions to TDM, while total editorial and review entries have been more variable over the years (see Figure 2 below). Importantly, memorials penned for deceased members of the field (3%) have also been featured in TDM across editorial eras, as well rarer materials from Robert E. Howard himself (6%). These contributions underscore the important inclusion of irregular miscellany in TDM over the years. The author extends a hearty thanks to the Robert E. Howard Foundation, and specifically www.howardworks.com for their tireless efforts to catalog the publication history of Robert E. Howard; nearly all data summarized here was procured from that resource. Data visualizations in this publication were generated in R (version 3.6.0; R Core Team 2019; https://www.r-project.org//). Many thanks also go to Josh Adkins for conversations and suggestions related to data visualization. Finally, the author extends a deep gratitude to the many editors of TDM for their many decades of service to pulp fandom. Luke E. Dodd is a professor, scientist, devourer of music, and collector of hobbies. He is one of the three hosts of The Cromcast, a podcast dedicated to the works of Robert E. Howard and other weird fiction (www.thecromcast.blogspot.com). He lives in Kentucky with his wife and son.

AUDIO ESSAY

By Jason Ray Carney Recently scholar Bobby Derie brought to my attention an interesting passage from a letter from H.P. Lovecraft to J. Vernon Shea. In this passage, Lovecraft admits to admiring Ernest Hemingway: "Hemingway is the sort of guy I intensely admire without any great impulse to imitate him. His prosaic objectivity is a very high form of art--which I wish I could parallel--but I can't get used to the rhythm of his short, harsh sentences." - H. P. Lovecraft to J. Vernon Shea, 18 Sep 1931, LJS 56 Initially, one cannot think of two more diametrically opposed writers. Hemingway the Literary Modernist hews closely, even quasi-journalistically, to a harsh reality principle. In novels such as The Sun Also Rises (1926) and short stories like "A Clean, Well-Lighted Place" (1933), Hemingway uses a narrative rhetoric shorn of all superfluidities to bring into stark focus the disenchanted, dehumanizing reality of interwar modernity. With spartan prose, Hemingway creates flawed and pitiful characters such as Jake Barnes, Francis Macomber, Santiago the Fishermen, men who are portrayed as defeated, emasculated, and undermined by the harsh conditions of their unromantic lives. Compare this oeuvre to Lovecraft the Pulp Sensationalist, whose work bridges every variation of the unreal genres of science fiction, fantasy, and supernatural horror. Lovecraft's dream stories are overripe with Dunsanian lyricism and baroque language. Lovecraft's Gothic pastiches adopt antiquarian affectations and have truck with a rhetoric of pulp spectacle, replete with ghouls, yawning graves, and lots of exclamation points. Finally, consider Lovecraft's science fiction masterpieces, such as At the Mountains of Madness (1936), loquacious tales that gush with pseudo-ethnographic thick description. In execution and style, these two writers could not be more different. But Lovecraft's admiration of Hemingway reminds us to consider these two writers' thematic similarities, their perverse preoccupation with the extent to which modernity disenchants the world, disinvests humanity of a sense of belonging in the cosmos; how modernity transforms the cosmos into a vacuum of meaninglessness. Consider the reflections of the protagonist from Hemingway's, "A Clean, Well-Lighted Place," a man who contemplates what he believes to be the bedrock foundation of the human condition: an undeniable fear of nothingness that can only be temporarily arrested by light. What did he fear? It was not fear or dread. It was a nothing that he knew too well. It was all a nothing and a man was nothing too […] but he knew it all was nada y pues nada y nada y pues nada. Our nada who art in nada, nada be thy name thy kingdom nada thy will be nada in nada as it is in nada. Give us this nada our daily nada […]. Hail nothing full of nothing, nothing is with thee. We hear the echoes of this philosophy of the ubiquity of fear in many of Lovecraft's famous, aphoristic asides in fiction, as well as in his criticism, not least from his opening to his literary historical survey of weird fiction, "Supernatural Horror in Fiction": The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown. These facts few psychologists will dispute, and their admitted truth must establish for all time the genuineness and dignity of the weirdly horrible tale as a literary form. Against it are discharged all the shafts of a materialistic sophistication which clings to frequently felt emotions and external events, and of a naively insipid idealism which deprecates the aesthetic motive […]. For both Hemingway and Lovecraft, fear of an all-consuming emptiness taints all of our human endeavors. Both writers are bards of the absurd, giving aesthetic form to humanity's alienation in the Western world between the wars. Blogger bio: Jason Ray Carney teaches popular literature and creative writing at Christopher Newport University. He is the co-editor of The Dark Man, the area chair of the "Pulp Studies" section of the Popular Culture Association, and the editor of Whetstone: Amateur Magazine of Sword and Sorcery. The Pavilion Blog is the companion blog of The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp Studies. It features brief, conversational reflections related to Robert E. Howard at around 500-600 words. Interested in contributing? E-mail the editors at [email protected] By Willard M. Oliver

In the third issue of The Dark Man, Rusty Burke published an article titled, “The Active Voice: Robert E. Howard’s Personae,” in which he demonstrated a clear pattern in Howard’s writing in that in order for him to write his stories, he first had to create a character and develop a persona around that character. “It wasn’t enough for him to relate stories about a character,” Burke wrote in the introduction to Post Oaks and Sand Roughs & Other Autobiographical Writings, “he had to relate them from within the character” (REH Foundation Press, 2019). As Howard himself told Lovecraft in a September/October 1933 letter, “I like to have my background and setting as accurate and realistic as I can, with my limited knowledge.” In The Dark Man article, Burke noted the three main personae for Howard were the Boxer, the Celt, and the Texan, while in the introduction to Post Oaks he adds one more persona, the one he developed to write his semi-autobiographical novel, the “Realist” or “Realism” persona. To this list, I wish to propose one more persona that, like the Realism persona, did not fully develop, but still found its way into many of his yarns and rimes; I am speaking of the Ancient Mesopotamian Persona. The early roots of this persona most likely came from reading the Bible, something his mother no doubt impressed upon him. In Howard’s letters to Lovecraft, he mentions Ancient Mesopotamia in five separate letters, such as a February 1931 letter in which he explained, “I somehow feel more a sense of placement and personal contact with Babylon, Nineveh, Askalon, Gaza, Gath, and the like, than I do with Athens or Rome.” In a follow-on letter in June, he even went so far as to write, “I have wondered at times if I number some Babylonian or Chaldean among my ancient ancestors, so strong at times [...] for it is only with the Mesopotamian countries that I feel any sense of placement.” It is possible that Howard was purposefully writing about Ancient Mesopotamia in these letters because he was endeavoring to create a new persona. Howard’s yarns that have a strong connection to Ancient Mesopotamia include the unfinished Solomon Kane story “The Children of Asshur,” as well as “The Fire of Asshurbanipal,” “The House of Arabu,” and “The Voice of El-Lil.” He also mentions Mesopotamia in such varied stories as “The Blood of Belshazzar,” “The Road of the Eagles,” “The Lion of Tiberias,” “Skull-Face,” “The Moon of Skulls,” and “The Gods of Bal-Sagoth.” In looking to Howard’s rimes, the evidence is clear that he had a fascination for Ancient Mesopotamia: “The Gate of Nineveh,” “Babel,” “Babylon,” “Babylon has Fallen,” “O Babylon, Lost Babylon,” “The Road to Babel,” “The Riders of Babylon,” etc. Although the topic of Ancient Mesopotamia sadly did not develop into a specific character, it clearly wove its way through some of Howard’s writing. Further research may clarify if this was merely a subject of fascination or an undeveloped persona. Blogger bio: Willard M. Oliver is a professor at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas. He is a member of REHupa, has recently published in The Dark Man, and is currently working on a biography of REH for the University of North Texas Press. The Pavilion Blog is the companion blog of The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp Studies. It features brief, conversational reflections related to Robert E. Howard at around 500-600 words. Interested in contributing? E-mail the editors at [email protected] By Bobby Derie

Conan the Barbarian #1 was launched by Marvel Comics in 1970...and before that, Conan appeared in an adaptation of “Gods of the North” in Star-Studded Comics #14 (Texas Trio, 1968)...and before that, down in Mexico, several series of La Reina de la Costa Negra ran through the 50s and 60s, starring a blond Conan alongside his pirate-queen Bêlit. They had first appeared together in the anthology Cuentos de Abuelito (1952). Before that...Gardner Fox had created a pastiche, Crom the Barbarian, who first appeared in Out of this World #1 (1950). Comic writers and artists would go on to publish the adventures of Conan and Kull, Bran Mak Morn and Solomon Kane, and Cormac Fitzgeoffrey, James Allison and Breckinridge Elkins, and others, albeit rarely. But these are all heroes. So, too, would they adapt and publish some of Howard's standalone horror stories. “Dig Me No Grave” was adapted in the revived Journey Into Mystery #1 (Marvel, 1972), “The Monster from the Mound” and “The Thing on the Roof” in Chamber of Chills #2 and #3 (Marvel1973)—but what about before that? What was the first Howard horror story adapted to comics? In the days before the Comics Code Authority was created in 1954, horror comics proliferated on the stands, each one trying to outdo the other in grue and ghastliness. The comics shared many writers, artists, and editors with pulp magazines, and “borrowing” plots from the pulps was common, without credit to the original authors, and they often ended up strongly altered along the way. H. P. Lovecraft’s “Cool Air” was discreetly adapted by EC as "Baby...It's Cold Inside!" in Vault of Horror #17 (1951), and his “Pickman’s Model” became “Portrait of Death” in Weird Terror #1 (1952). They borrowed from Robert E. Howard too. “Skulls of Doom!” in Voodoo #12 (1953) is very obviously, albeit loosely, based on the story “Old Garfield’s Heart” which had first been published in Weird Tales (Dec 1933). The parallels are uncanny: a doctor is called to the beside of a dying old man, in whom an alien organ belonging to an old god resides—and must be returned. However, the adapters took Howard’s simple and powerful story and give it a few twists. Instead of the heart, the organ is the brain—an undying brain from the Egyptian priest Vishnu, who was made a god after his death. In a typical pre-Code horror morality play, the unscrupulous doctor steals Vishnu’s brain—and puts it in his own skull. Which works out great, until Vishnu returns to reclaim his brain. There may be some earlier adaptation tucked away in the moldering pages of some other pre-Code horror comic, and few of the writers and artists of that era could come close to capturing the magic of Howard’s prose, even if they borrowed his ideas. But for those who want to read “Skulls of Doom!”, the comic has passed into the public domain, and may be read for free. Blogger bio: Bobby Derie is a scholar of pulp studies and weird fiction; the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard and Others and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos. The Pavilion Blog is the companion blog of The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp Studies. It features brief, conversational reflections related to Robert E. Howard at around 500-600 words. Interested in contributing? E-mail the editors at [email protected] |

Details

CategoriesArchives

June 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed